1Parliamentary corpora are of different sizes and contain data of different modalities (written, spoken, gestural) and time periods in one or multiple languages. Although parliamentary debates are mainly provided as written texts (e.g., The Danish Parliament Corpus), they are sometimes also accessible as audio/video recordings coupled with corresponding transcriptions (e.g., Czech Parliamentary Meetings). When used as a diachronic source, a parliamentary corpus enables in-depth research of linguistic and societal change over time. Most parliamentary corpora have rich metadata about the speeches (e.g., date of the speech, duration of the speech, agenda item to which the speech is related) or the speakers (e.g., gender, age, education, political affiliation, institutional role) which offer valuable insights into the context on the studied phenomenon (see Alasuutari et al., 2018; Demmen et al., 2018).

4.1 Parliamentary discourse

1Parliaments are institutions governed by specific rules and conventions (see for example Erskine May, a description of the UK parliamentary procedure). These are shaped by sociohistorical traditions that influence the organization and operation of the parliament and also extend to language use, such as conventions for turn-taking or forms of address. These conventions, however, are not necessarily shared among different parliaments; e.g., interruptions are strictly prohibited in the Greek Parliament, whereas in the UK Parliament these are common and often not sanctioned (Ilie, 2017), which needs to be taken into consideration when forming queries or interpreting the results. Therefore, whenever this type of discourse is investigated, it is particularly important to understand the circumstances it was produced in.

4.2 Faithfulness of the records

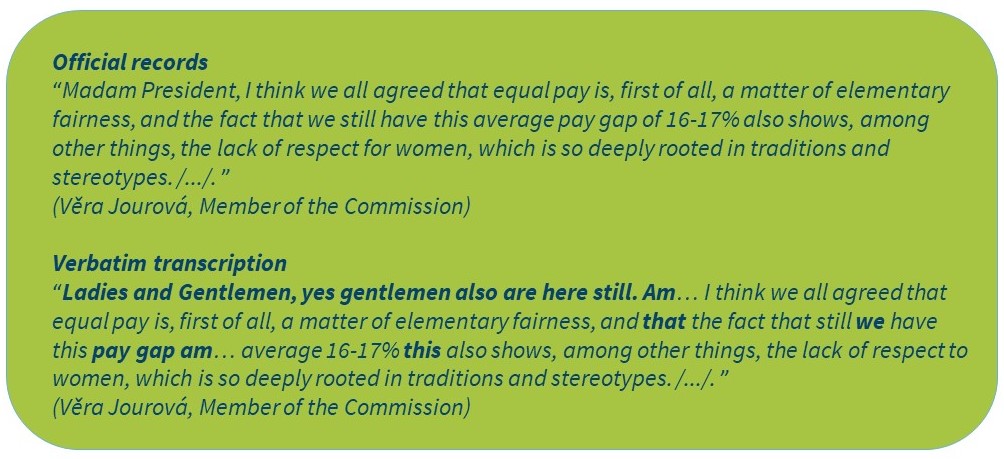

1It should be noted that officially released records of parliamentary debates are not 100% verbatim transcriptions, and that minute-taking practices vary through history and across countries. Editing usually involves elimination of some typical characteristics of spoken language but may also include other interventions, such as the elimination of obvious language or factual errors, dialectal or colloquial expressions, and rude and obscene language. Editing guidelines are mostly not made public, which can substantially hinder research (for more source criticism, see Mollin, 2007; Rix, 2014). Furthermore, speeches by MPs are often, although not in all parliamentary traditions and all types of parliamentary sessions (interpellations, debates, question time, etc.) prepared in advance (i.e. written-to-be-spoken), which has a big impact on their stylistic features. These peculiarities together with the broader sociohistorical context always need to be taken into account when defining research questions, methodology and the interpretation of the results.

2Figure 2 shows an illustrative comparison of the official records of a speech by Věra Jourová , a Czech politician and European Commissioner for Justice, Consumers and Gender Equality (2014-2019) at the plenary session debate on the gender pay gap from 1/5/2017 published on the website of the EU Parliament, together with a verbatim transcription of the video clip of her speech created for this tutorial. A quick look at the differences in the two transcripts shows that transcriptions of EU Parliamentary debates might not be the best resource for studying the use of determiners, frequency of hesitations or false starts, or even the use of spontaneous humour in parliamentary speech.

4.3 Know your research dataset

1In order to make the best use of any given corpus, to formulate search queries correctly and interpret the results appropriately, it is important to understand what the selected corpus contains, how it was constructed and annotated, and what its limitations are. The level of annotation varies from corpus to corpus, so the details for the selected corpus should always be checked. Such information is typically found on a dedicated webpage (e.g., Corpus of Historical Low German), inside the concordancer through which it is made available (e.g., Hansard in the concordancer of Brigham Young University) or in the repository where the corpus is archived (e.g., ParlaMeter-hr in the CLARIN.SI repository). You can read more about the encoding and annotation of parliamentary data in the Parthenos training module on the collections of parliamentary records.